What happens when I sleep?

This is the second of three blogs about sleep. In the first (https://lemonstolemonade.co.uk/news/insufficient-sleep-is-bad-for-your-mental-health-psychotherapy-counselling) we outlined some of the adverse effects on mental health of getting poor sleep. Here we describe what normally happens in healthy sleep. As you’ll see, it’s complicated! In the third we’ll outline some of the things you can do to remove obstacles to your getting a good night’s sleep.

Getting off to sleep

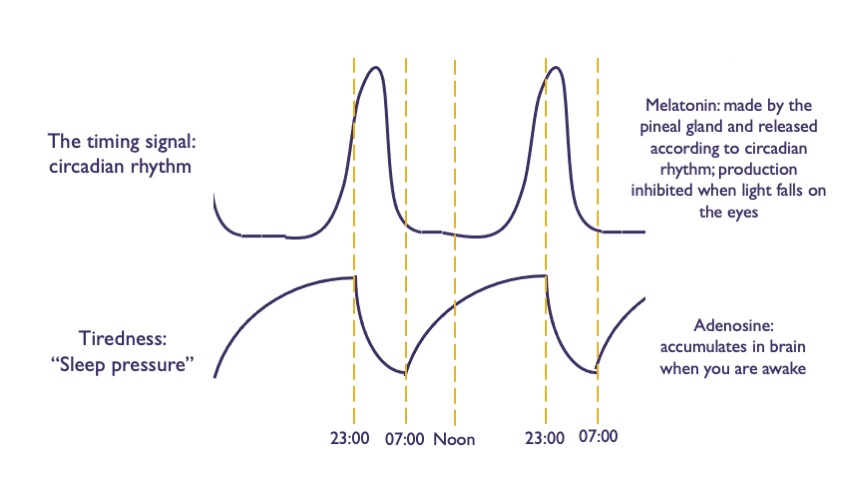

The first requirement to be able to fall asleep is that you feel tired. In sleep science, feeling tired is known as “sleep pressure”. When you’re awake a chemical called adenosine accumulates in your brain. The more adenosine, the more tired you feel and the more sleep pressure you experience. You’re likely to feel ready to sleep once the level of adenosine has built up for twelve to sixteen hours. Once you fall asleep, the amount of adenosine circulating in your brain quickly reduces. You can see how your adenosine level changes during the day in the first chart below. However, there are ways we can mess with the way adenosine regulates our sleep. For instance, if you take a nap during the day, this will reduce your sleep pressure and make it more difficult for you to get to sleep in the late evening. Also, caffeine blocks the function of adenosine, even many hours after you’ve ingested it, and can be a powerful cause of difficulty getting to sleep.

The second requirement to be able to fall asleep is a timing signal generated by the body’s internal clock, which generates a daily “circadian” rhythm that regulates many aspects of bodily function, including sleep. The timing signal to the rest of the brain is carried by another chemical, melatonin. Melatonin is made and stored in the pineal gland whenever light falls on the eyes. It is released a few hours after dusk when light levels are much lower (see the first chart). This rapid rise in melatonin levels within the brain acts as a daily signal that it’s time for sleep. As the chart shows, we fall asleep when high levels of adenosine coincide with rapidly rising levels of melatonin. The timing signal gradually accommodates to seasonal differences in day length, but humans have invented three effective ways to mess with it. The first is international travel across time zones: “Jet lag” occurs because it takes a week or so for the timing signal to adjust, and in the meanwhile, the peak of melatonin release can be out of synchronisation with the local day and night times. The second is the twice ritual yearly moving clocks backwards and forwards, which leads to disrupted sleep for several days for millions of us. The third is shift work, especially patterns of shift work that vary frequently.

What goes on when we’re asleep?

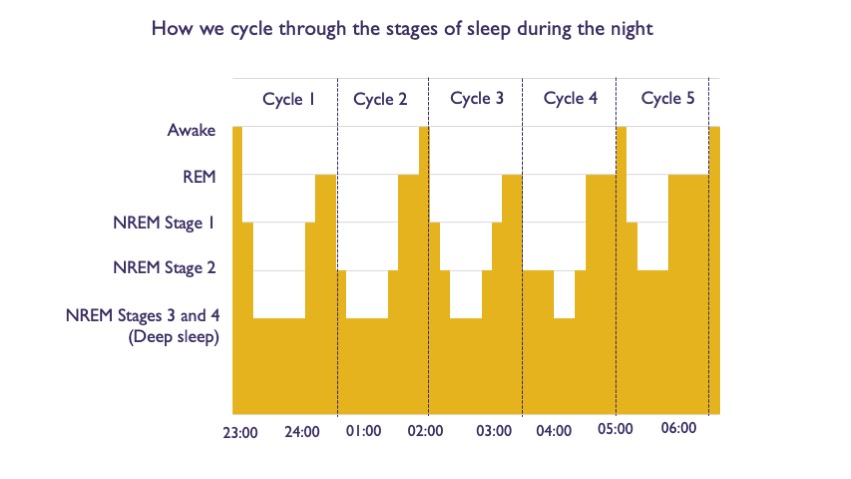

Not all sleep is the same. During the night, we cycle between two main types of sleep: Rapid Eye-Movement (REM) sleep, and Non-Rapid Eye-Movement (NREM) sleep. There are four stages of the latter: stages 1 and 2 are known as “light sleep”, and stages 3 and 4 are known as “deep sleep”. You can see how we cycle between these stages during the night, approximately every ninety minutes as adults, in the second chart.

Deep NREM sleep performs a vital function. Each day, we form many, many new memories; far too many to keep in the long term. During deep NREM sleep, our brains sift through these, deciding which new memories are relevant and worth transferring to our long-term memory store, and which are irrelevant and can be discarded. That’s the reason why most of us can’t remember what we ate for dinner or what we were wearing on a particular date last year (unless that day had a particular significance, like the wedding of someone we’re close to).

REM sleep appears to serve a different function. It’s when we process the various emotions we’ve experienced during the day and attach our memory of these emotions to our memories of events. If we wake up from REM sleep there’s a good chance we’ll be briefly aware of dreams we were having; these are thought to be part of the processing of the emotional content of our recent experiences.

If you look closely at the second chart you’ll notice something else: the proportion of NREM sleep to REM sleep changes as the night goes on. When we first fall asleep, we have a long period of deep NREM sleep, and only a short period of REM sleep. Later in the night, the amount of deep NREM sleep per cycle decreases and the amount of REM sleep per cycle goes up.

Do we all need the same amount of sleep?

No, we don’t. The amount of sleep we need changes as we grow older. New-born babies sleep for about sixteen hours a day; ten to thirteen year olds typically sleep for around ten hours; adults need somewhere between six and nine hours, and those aged seventy and over usually sleep for around six hours or less.

Neither do we all naturally sleep at the same times. Sleep science has identified three “chronotypes”: groups of people with different overall sleep timing. “Larks” tend naturally to go to bed early and get up early; “Owls” tend naturally to stay up late and get up late; while “Ambivalents” are naturally somewhere in between. It’s worth recognising what your chronotype is: having a mismatch between your chronotype and the requirements of your occupation or your lifestyle can lead to problems with sleep.

What if I’m having difficulty sleeping?

Our next blog will outline some of the things you can do to remove obstacles to your getting a good night’s sleep. If you’re consistently not getting good sleep, there’s a proven answer; and no, it’s not sleep medication, which is only a short-term fix. The top recommendation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) is a psychological therapy, Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I). which we offer at Lemons to Lemonade. If you recognise you’re sleep-deprived and want help, you can contact us by email at contact@lemonstolemonade.co.uk or by phone on 07376 010506.